Amish Quilts

Oct 7, 2016 - Feb 4, 2017

And the Crafting of Diverse Traditions

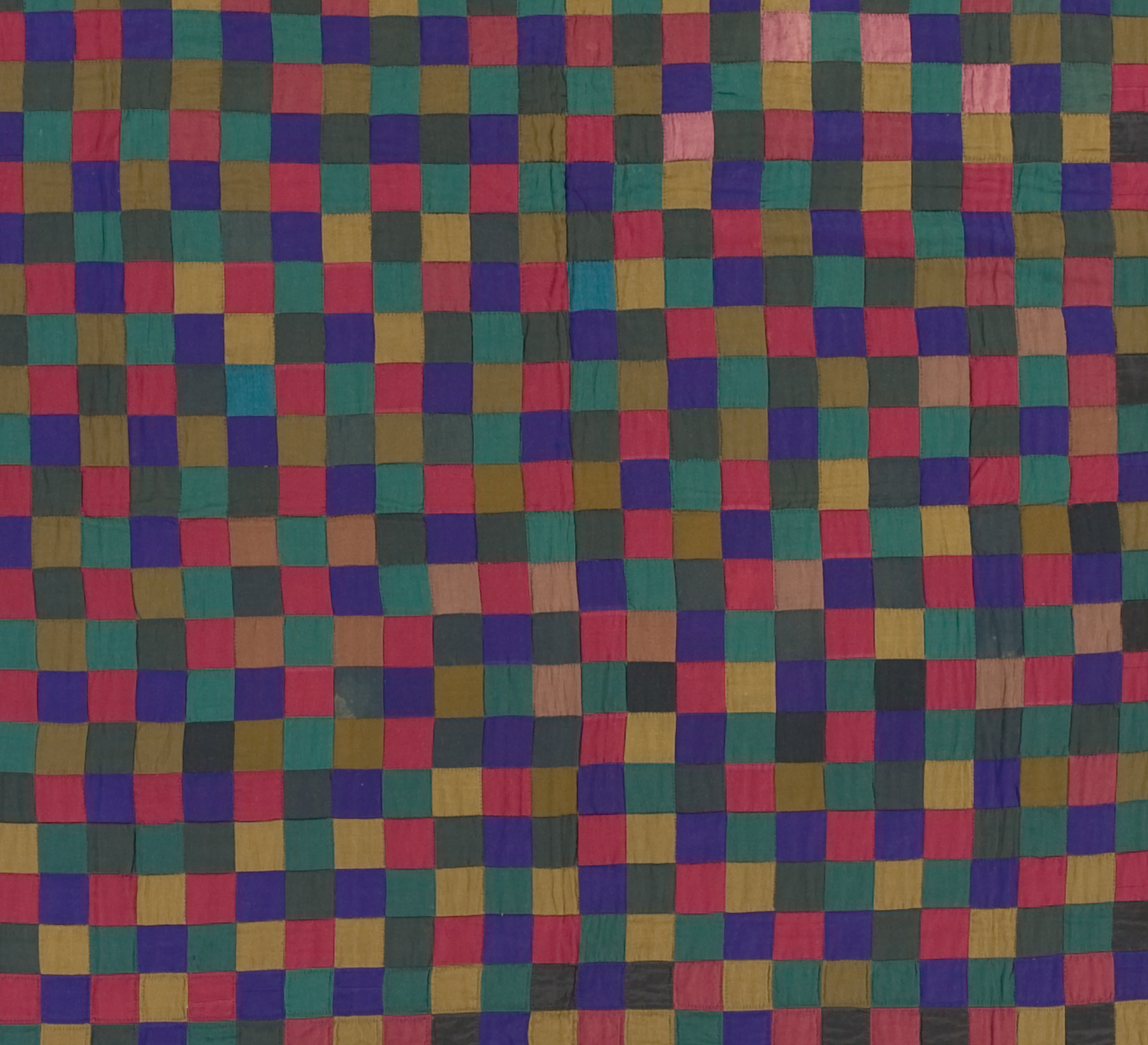

Fifty years ago, no one bothered pairing the adjective Amish with the noun quilt. Few people outside Amish settlements knew there was anything distinct about the types of patchwork bedcovers Amish families kept folded in cedar chests or displayed on their guest beds. Yet in the intervening years, Amish quilts have shifted in status from obscurity to sought-after artworks.

Amish women have been making quilts since the late 1800s, but only in the 1970s, when art enthusiasts began comparing Amish quilts to abstract modernist paintings, did Amish quilts become “cult objects.” Collectors, curators, and designers loved the solid-colored fabrics and bold, graphic designs of classic Amish quilts, which helped transform these textiles into affordable works of art. Amish entrepreneurs responded to the quilts’ newfound popularity, making quilts to sell directly to outsiders. “Amish,” in turn, functioned as a brand name, appealing to those who wanted a handmade, authentic quilt.

The craft has never fossilized, but has been a living, evolving, and diverse tradition, adapted by creative quiltmakers, capitalized upon by businesswomen eager to earn a livelihood, and embraced within both Amish communities and the broader artistic and consumer worlds