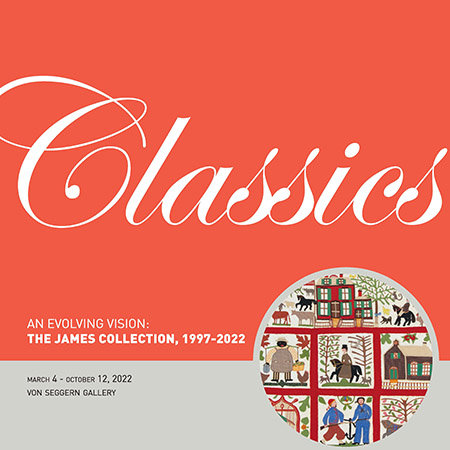

Reconciliation Quilt

Lucinda Ward Honstain and/or Emma Honstain Bingham

Brooklyn, New York

November 18, 1867

Cotton; hand pieced, appliqued and embroidered, hand quilted

Ardis and Robert James Collection, IQM 2001.011.0001

The "Reconciliation Quilt” was made by Lucinda Ward Honstain of Brooklyn, New York in 1867, likely with the assistance of her daughter Emma Bingham. Imagery in this unique album quilt highlights the racial, social and economic diversity of the years immediately following the end of the Civil War, as well as images of Lucinda’s Brooklyn neighborhood.

Jeff Davis and Daughter

A block reading “Jeff Davis and Daughter,” portrays the former president of the Confederate States of America standing with one of his daughters. On May 13, 1867, in a gesture of reconciliation, a northern judge released Jefferson Davis on bail from Virginia’s Fort Monroe. Northerners were divided over the decision, but many felt releasing Davis was an important step in uniting the North and South. Was Lucinda hoping to do her part to promote reconciliation?

Brawl in the Fifteenth Ward: The Honstain Family War Renewed

The detailed imagery of Honstain’s quilt suggests a serene life, with images of her Brooklyn home and patriotic portraits of her husband and son-in-law. Reality was far from calm, however. Lucinda and her husband were the topic of numerous newspaper articles, including a report of a brawl in the street in front of her home after she and her husband separated. A year later they divorced, though Lucinda referred to herself as a widow in later U.S. census records.

Honstain’s Military Service…or Disservice?

John Honstain served twice during the Civil War. Family records indicate that, seven months after enlisting in April, 1861, he was arrested and court-martialed, after cheating other soldiers out of money intended for their uniforms. He was allowed to resign. He enlisted again in 1862. In 1863, serving as a Lieutenant in the 132nd Regiment of the New York Volunteers, he ventured behind enemy lines and was captured. He told a story of a daring escape, but upon his return he again faced charges for desertion. His was dishonorably discharged on May 31, 1865.

Elephants, Camels and Walruses… in New York City?

Honstain’s quilt holds a variety of animals, many of them typically found in a farmyard. But she also included exotic animals such as elephants, camels, and walruses. Where would she have encountered them? Perhaps at the American Museum…or in Central Park!

Showman P.T. Barnum opened the American Museum in New York City in 1841. The museum was decorated with huge pictures to draw in crowds eager to see exotic animals. The museum’s lecture hall featured performances involving whales, hippos, monkeys, snakes, and even a kangaroo. The Central Park Menagerie opened officially in 1865, but hundreds of animals, including camels and alligators, had already been donated to the collection.