From Kente to Kuba

Dec. 7, 2018-May 12, 2019

Stitched Textiles from West and Central Africa

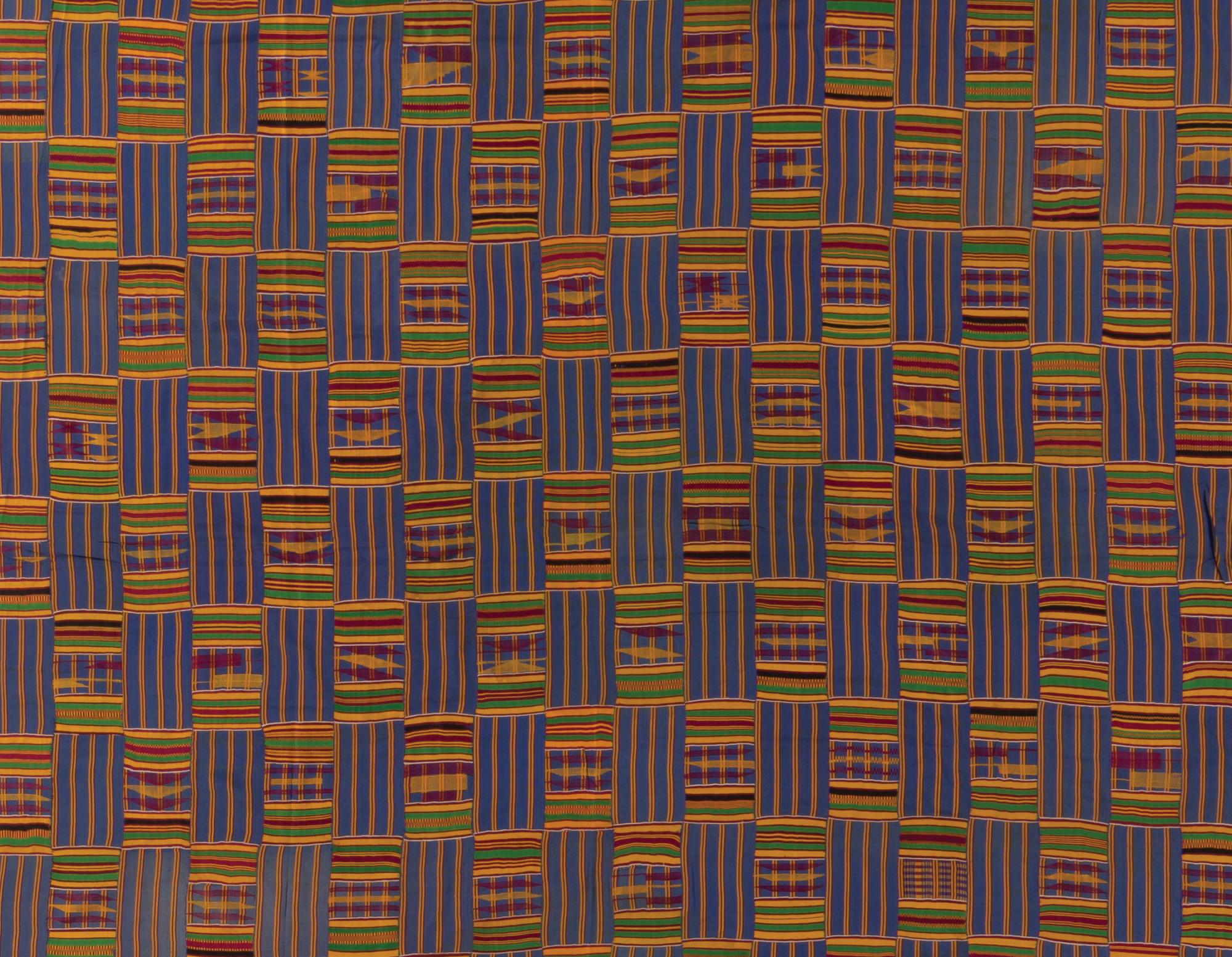

In Africa, fabric is useful, valuable, and symbolic. It speaks to identity, group affiliation, and prestige. It is colorful, patterned, and visible everywhere: at community gatherings, in the marketplace, and in the home. The ubiquity of fabric means that few forms of material culture can compete with it for status. For instance, although sculpture has received more scholarly and popular recognition outside of Africa, art historian Sylvester Okwunodu Ogbeche points out that at home, African textiles such as kente and Kuba cloth are more highly regarded: “These important textiles have a universal recognition that African sculpture can only dream of.”

Although stitched textile techniques such as patchwork, appliqué, and quilting are less common in Africa than weaving, dyeing, and printing, the stitching arts are greatly prized among some ethnic and regional groups. Kente cloth from Ghana is made by sewing long, woven strips together to create large fabrics for garments. Kuba cloth from the Democratic Republic of the Congo is a ceremonial raffia fabric constructed using a number of techniques, including patchwork and appliqué. Masquerade costumes from Nigeria feature plentiful stitchwork, and enable villagers to “transform” into spirits during rituals and festivals. Although Africa does not have an indigenous quiltmaking tradition, contemporary Nigerian artisans have developed a new, American-style patchwork bedspread using traditional indigo-dyed adire cloth.

The stitched textiles in this gallery represent an important niche in the rich, ever-evolving world of African textiles.